The Quiet Land

The Quiet Land

The title of this book was inspired by a poem that I quote at the end of the novel.

In a quiet water’d land, a land of roses,

Stands Saint Ciarán’s city fair;

And the warriors of Erin in their famous generations

Slumber there.

Written in the fourteenth century, about a hundred years after the novel is set, it captures a sense of the peace that you feel today at Clonmacnoise: “A quiet water’d land, a land of roses.” But beneath that quiet, literally beneath your feet, lie the bones of the great and ferocious warriors of Irish history and legend: “Battle-banners of the Gael that in Kieran’s plain of crosses / Now their final hosting keep.” It struck me that this had actually been a most UNquiet Land.

The original poem was written in Irish by Angus O’Gillan (also called Aongus Ó Giolláin, Enoch O’Gillain, and Enoch o’Gillan), but it is best known from a brilliant late-19th century translation by T.W. (Thomas William Hazen) Rolleston (1857-1920).

Rolleston’s translation first appeared in William Butler Yeats compilation A Book of Irish Verse, published in London in 1895, where Yeats said the poem was “so purely emotional that it must stand an example of the Gaelic lyric come close to perfection.” (Rolleston and Yeats had a complicated relationship; in his memoirs, Yeats called Rolleston his “intimate enemy.” The two would meet at gatherings of Yeats’s London-based “Rhymer’s Club,” at “Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese” pub in the 1890s.)

The poem, in the translation by Rolleston, first became widely known when it was included in the 1919 edition of The Oxford Book of English Verse: 1250-1900, edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch. This important anthology sold almost a half-million copies in its first edition and was extremely influential in introducing poetry to a new audience at the turn of the twentieth century.

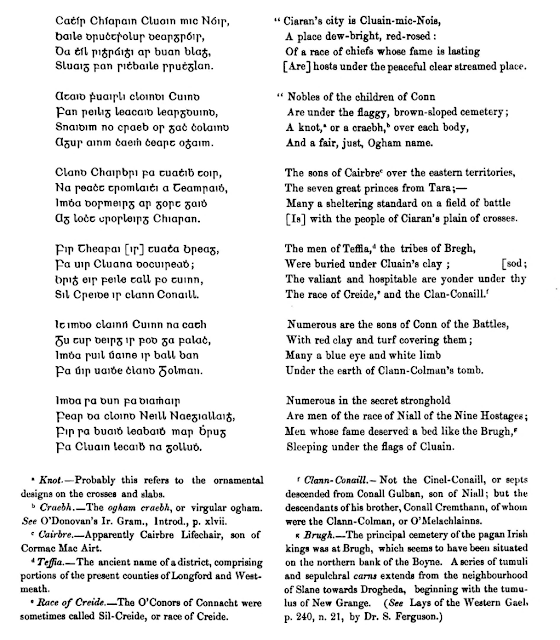

Rolleston’s source was almost certainly a 19-stanza version of the poem, in Irish and English, which was included in the 1897 Christian Inscriptions in the Irish Language, “Chiefly Collected and Drawn by George Petrie, and Edited by M. Stokes.” (There is a link below where you can read the complete poem in this version.)

The antiquarian Petrie found the poem in “the Rev. Dr. Todd’s list of Irish manuscripts preserved in the Bodleian Library (Rawlinson, B. 486. fol. 29),” which describes the “tribes and persons interred at Clonmacnoise, written by Enoch O’Gillan, who lived on the borders of the River Suck, in the county of Galway.” (The author identifies himself in the last stanza.)*

Petrie thanked “Mr. Wm. M. Hennessy for the translation and notes with which he has enriched it.” I am including an illustration of the first six stanzas with Hennessy’s notes.

My favorite stanza here, which Rolleston didn’t incorporate into his version is the last one shown on this page:

Numerous in the secret stronghold

Are men of the race of Niall of the Nine Hostages;

Men whose fame deserved a bed like the Brugh,

Sleeping under the flags of Cluain.

In his note “g” Hennessy tells us that “men of the race of Niall of the Nine Hostages” (the famous ancestor of the O’Neil clan), were important enough to have been buried in the great Paleolithic tombs like New Grange, but still chose Clonmacnoise, for the nearness to the relics of St. Ciarán. (The word “Cluain” is used here as an abbreviation for Clonmacnoise, which is spelled Cluain Mhic Nóis in Irish.)

I’ll let Prof. Gregory A. Schirmer have the last word before I conclude this blog with the complete text of Rolleston’s translation. In his excellent book Out of What Began: A History of Irish Poetry in English, Schirmer gives us a perfect context for the Celtic/Romantic poetry which appeared in the world of Yeats, Lady Gregory, and Douglas Hyde.

“What is most striking about this poem, especially in the context of the literary revival’s construction of an Irish past, is the way in which it reads this landscape generally associated with Ireland’s Christian past—Clonmacnoise was once one of the centers of European Christianity—in almost exclusively pagan terms, nearly displacing the monastic community founded by St. Kiernan in the sixth century with the pagan culture that lies buried beneath it. The Dead of Clonmacnoise exemplifies the general tendency of the revival to celebrate Ireland’s pagan past at the expense of its Christian one, a strategy of obvious political advantage to a movement directed for the most part by a class alienated from contemporary Irish Catholicism.”

This is the O’Gillan/Rolleston poem as it appears in the Oxford Book of English Verse:

T. W. Rolleston. b. 1857

849. The Dead at Clonmacnoise

FROM THE IRISH OF ANGUS O'GILLAN

IN a quiet water'd land, a land of roses,

| |

Stands Saint Kieran's city fair;

| |

And the warriors of Erin in their famous generations

| |

Slumber there.

| |

There beneath the dewy hillside sleep the noblest

| |

Of the clan of Conn,

| |

Each below his stone with name in branching Ogham

| |

And the sacred knot thereon.

| |

There they laid to rest the seven Kings of Tara,

| |

There the sons of Cairbrè sleep—

| |

Battle-banners of the Gael that in Kieran's plain of crosses

| |

Now their final hosting keep.

| |

And in Clonmacnois they laid the men of Teffia,

| |

And right many a lord of Breagh;

| |

Deep the sod above Clan Creidè and Clan Conaill,

| |

Kind in hall and fierce in fray.

| |

Many and many a son of Conn the Hundred-Fighter

| |

In the red earth lies at rest;

| |

Many a blue eye of Clan Colman the turf covers,

| |

Many a swan-white breast.

|

Note: O’Gillan and Rolleston each lived for a time within a relatively short distance of Clonmacnoise. O’Gillan identifies himself as originating “by the stream of the Suck,” the river that forms the border between Rosscommon and Galway counties today, and runs into the Shannon just below Clonmacnoise. Rolleston was born in Shinrone, County Offaly, about 25 miles southeast of the monastic ruins.

Sources:

Christian Inscriptions in the Irish Language, “Chiefly Collected and Drawn by George Petrie, and Edited by M. Stokes” (Dublin: The University Press for the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association, 1872). This book is now available online at: https://archive.org/details/ChristianInscriptionsInIrishV1/page/n9/mode/2up

Information on Clonmacnoise and this poem are discussed in the very first pages.

Comments

Post a Comment