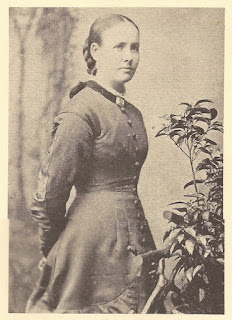

The Real Lizzie Manning

The heroine of my first three novels, Lizzie Manning, is named after my great-grandmother, Elizabeth O’Neil Manning, who died one hundred years ago in Homestead, Pennsylvania. She was 53 years old and a victim of the influenza pandemic that spread catastrophically around the globe between 1918 and 1920.

Elizabeth, two of her five daughters, and a newborn granddaughter, all died within one week starting on 27 January 1920. My grandmother, Marie Manning Newman, was then living in Detroit; she was pregnant and gave birth to my aunt Gladys on the 10th of February. She learned of the deaths of her mother, sisters, and niece in an extraordinary 14-page letter, written by her sister Agnes. Then 23 years old and still living at home, Agnes was the primary caregiver of her mother and sister Anna through their short but deadly illnesses.

Their older sister Elizabeth (called “Sis”) was married and lived in an apartment nearby with her husband and toddler son. She was the first one to get sick and the illness progressed so quickly that she went into premature labor and died within a week of showing the first symptoms. In her letter, Agnes describes how Sis’s body was brought back to their parents’ home and laid out in her wedding dress on the dining room table. The elder Elizabeth had to be carried downstairs to see her daughter for the last time, and she died the next day.

Agnes was responsible for dressing the corpses of her mother and two sisters for their wakes and funerals and arranging their hair, which she described in her letter. (She told Marie that their mother wore the slip she had sent her for Christmas.) This letter puts a very human face on the grim statistics. The Manning deaths were among the last casualties in Pennsylvania of the pandemic that killed more than 40,000 people in the state, 625,000 in the US, and 50-100 million around the world. In her letter Agnes wrote: “I can’t understand how in the world I never contracted it. I’m glad I didn’t know at the time it was influenza or I might have been frightened into it.” (Agnes was tougher than she admitted. She lived to be 99 and died in 1996.)

My grandmother knew the impact the disease was having on her hometown community from the fall of 1918. In November of that year she received a letter from her sister Anna telling her of “39 deaths in our church this last month with the flue,” a terrible community tragedy.

On 31 January 1920, the day Elizabeth Manning died, the Homestead Daily Messenger reported that the “flu epidemic all over the U.S.” was now “well in hand,” though there were still lingering cases across the country from New York to Oregon. Two weeks later, the Pittsburgh Gazette Times, reported that the Pittsburgh Controller, E.S. Morrow, was calling for $50,000 to aid in a health campaign as deaths continued. “It may not be as virulent as two years ago,” he said, “but from the daily record of deaths and the number of persons I know who are afflicted it is bad enough.”

Today, with news of the coronavirus—another potentially catastrophic pulmonary infection—spreading around the world, I am reminded of the tragedy that just such an illness caused in my family one century ago this week.

Wash your hands! Cover your sneezes, and stay well.

There are a number of books available that describe this event. I recommend Gina Kolata’s Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It (Atria Books: 2001).

Comments

Post a Comment